Afternoon Tea & Tea DancesAnna Maria Russell, the seventh Duchess of Bedford, introduced the concept of afternoon tea one summer in the early 1840s, at her country estate. English high society didn’t dine until 8:30 or 9 p.m.—even later in the summer—and she needed something to tide her over during the stretch between what was then a light lunch and dinner. To quell the “hungries,” she ordered her maid to bring her what we would call a snack—a small meal of bread, butter, cakes and tarts and a pot of tea—at 4 p.m. daily. It was brought secretly to her sitting room, as incremental eating was unseemly for a royal.

*Americans often confuse afternoon tea with high tea. High Tea is a hearty working class evening meal, generally served around 6 p.m. It generally includes roast beef or leg of lamb, pastry or custard for dessert, and tea. Although it sounds similar, high tea is a world away from the fashionable circles of afternoon tea.

If you’re near Bedfordshire, England, take a trip to the ancestral estate, Woburn Abbey, where you can take tea in Anna Maria’s own Blue Drawing Room, below.

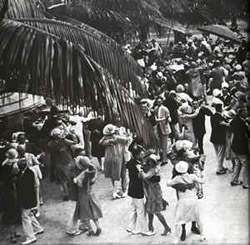

Tea Becomes The Social Convention In 1842, a well-known actress named Fanny Kemble first heard of afternoon tea, and did not believe the custom had been practiced prior to that date. Within a few years, a complex set of rules and etiquette developed surrounding the social custom of women visiting each other for tea. In the 1840s, upper middle class and upper class women commonly held at-home teas. Each chose a permanent day of the week to hold at-home hours, and would then send announcements to friends, relatives and acquaintances. Unless regrets were sent, it was expected that invitees would attend. On that particular day of the week, she would remain at home all day to receive visitors. Conversation, after the model of the French salon, was the primary entertainment. Tea, cakes and finger sandwiches were served. There was at least one person holding an at-home day on any given day, the social fabric of the community was established, and most women saw each other almost every day at different houses. The hostess would announce when tea was served, and would take a seat at one end of the table to pour tea for her guests. The eldest daughter of the household, or the closest friend of the hostess, poured coffee or hot chocolate. The hostess also added the sugar and milk or lemon to the tea per the guest’s preference. Why not a buffet? Tea and sugar were more common and affordable by the 1800s, but as consumable luxuries they still represented wealth and were controlled by the hostess (tea was stored in locked tea caddies to which only the woman of the household held the key, and did not become widely available and affordable to the working classes until the middle to late nineteenth century, with the introduction of cheap black tea from Sri Lanka). The upper classes, wealthy enough to hire servants, had them pour the tea, and guests could add their own sugar, milk or lemon. By releasing control over dispensing tea and sugar, the upper classes demonstrated their wealth and ability to buy as much of these items as desired. The Tea Dance

Continue To Page 8: Clipper Ships & The American Tea Trade Return To Article Index At The Top Of The Page

|

The Nibble Blog

The Latest Products, Recipes & Trends In Specialty Foods

The gourmet guide you’ve been waiting for. New food adventures are served up daily. Check it out!

Food Glossary

Our Food Directories Are "Crash Courses" In Tasty Topics

Your ultimate food lover’s dictionary packed full of information and historical references. Take a look!