The first pasta was not spaghetti, but dumplings—the style Marco Polo saw during his trip to China. Photo by Joan Ho | SXC.

October 2007

Last Updated February 2012

|

|

The History Of Pasta

Page 2: It Traveled From China To Arabia To Italy

This is Page 2 of a five-page article; here, an introduction to pasta history. Click on the black links below to visit other pages.

The Middle Ages

Documents from the 12th century describe something like a factory in the area of Palermo, that exported dry pasta to regions of southern Italy. By the 1300s, dried pasta had spread to Genoa. Genovese sailors, among the best traders in the Mediterranean, brought the pasta north from Sicily. Pasta was very popular for its nutrition and its shelf life, and was ideal for long ocean voyages.

From the port of Genoa it traveled to other areas, including Provence and London. Genoa became a trade center, and then a producer, of dry pasta.

Marco Polo: The Historic Truth

What about the belief that the great Venetian explorer, Marco Polo, introduced pasta to Italy from China?

There is much historic record to show otherwise. While Marco Polo was visiting the Far East (he set out in 1271 and returned in 1295), in 1279, the last will and testament of one Ponzio Baestone, a Genoan soldier, was written. In this will, Baestone bequeathed “bariscella peina de macarone,” a small basket of macaroni.

We know from this and other written records that pasta was in Italy before Marco Polo’s return.

Dry pasta was unknown to the Chinese at that time. What Polo did bring back in 1295 was rice flour pasta, the perishable, soft kind from which Chinese dumplings had been made since 1700 B.C.E., and the concept of stuffed pasta.

Today the “dumpling” style of pasta is manifested in ravioli, gnocchi and other preparations using regular wheat flour, eggs and water. It is referred to as “dumpling”-style or soft pasta, even when it is dried hard. That is Marco Polo’s legacy.

|

|

These steamed, meat-filled dumplings, or tangbao, may be similar to what Marco Polo introduced to Italy when he returned to Venice from China. Flatten them out a bit, and they’d look similar to modern, handmade Italian ravioli. Photo by Joan Ho | SXC.

|

Pasta Bequeathed In A Will

That a basket of pasta was bequeathed in Ponzio Baestone’s will shows that pasta was still a luxury in the 13th century. By 1400 it was being produced commercially, in shops that retained night watchmen to protect the goods.

Why was pasta so costly? Labor! Barefoot men had to tread on dough to make it malleable enough to roll out. The treading could last for a day. This is because milled durum wheat, semolina, is granular like sugar, not powdery like other flours. It must be kneaded for a long time (which is why it is not used in homemade pasta—the motors of home machines are not sufficient to process it). The dough then had to be extruded through pierced dies under great pressure, a task accomplished by a large screw press powered by two men or one horse.

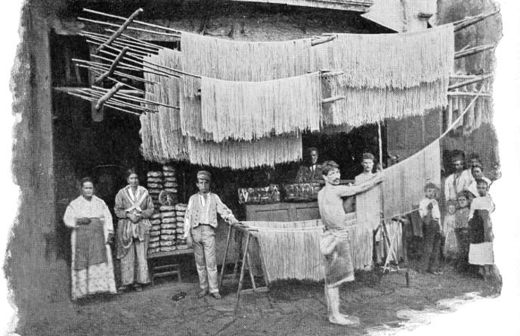

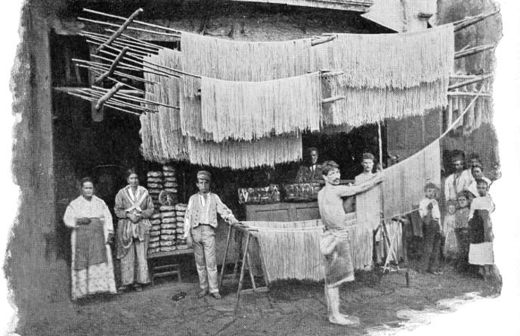

And then, each strand was cut by hand and hung to dry, as you can see in the photo below.

Photo from more than 400 years after the commercial production of pasta began (the first photography was taken in 1827 by French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Photo courtesy LifeInItaly.com).

Sicily In Pasta History

Durum wheat was well-suited to the soil and weather of Sicily and equally to Campania, the region around Naples. It was grown in large quantity in southern Italy. Naples also had an ideal climate for drying pasta: mild sea breezes alternating with hot winds from Mount Vesuvius. This ensured that the pasta would not dry too slowly and become moldy, or dry too fast and crack. A thriving pasta industry developed in the region.

Continue To Page 3: The Pasta Renaissance

Go To The Article Index Above

Content copyright © 2005-

|