The Scharffen Berger logo features an ibex mountain goat and three stars. All photography by Saidi Granados.

|

PETER ROT is the THE NIBBLE’s chocolate specialist.

|

September 2008

|

|

Scharffen Berger Chocolate

Page 2: Origin Chocolate

This is Page 2 of a six-page article. Click on the black links below to visit other pages.

Origin Chocolate (or “Single Origin Chocolate”)

The buzzword among the inner circle of connoisseurs, origin chocolate, has been synonymous with “the best” for twenty years. In 1988, Valrhona launched the concept with its breakthrough bar, Guanaja, a 70% cacao bar made from beans exclusively from Honduras. But origin chocolate has really become the focus of the gourmet chocolate world within the last five years, as chocolate from such esteemed French makers as Michel Cluizel and Domori gradually gained distribution in the U.S., eventually winning over many taste buds with the variety of flavor experiences that different origins and cacao contents provide.

Today, one can find chocolate sourced from such countries as Colombia and Peru, specific regions as Guaranda (Ecuador) and Chuao (Venezuela) and even single plantations such as Hacienda Concepción (Venezuela) and Ampamakia (Madagascar). You may begin to notice a comparison of cacao beans to wine grapes; Valrhona and Chocolove even make “vintage” chocolate bars from a single year’s cacao harvest—a perfectly legitimate way to look at cacao—or tea, coffee or any agricultural crop, since weather and other factors will impact the flavor of each year’s harvest.

The number of origins listed above is a tiny fraction of what is available on the market. And it’s not only artisan producers that make origin chocolate. Powerhouses such as Hershey and Lindt have captured a sizable market share, ensuring far-reaching availability of origin chocolate. Hershey’s Cacao Reserve brand features the origins Ecuador, Dominican Republic, Sao Tome and Java, while Lindt showcases Madagascar and Ecuador in its Excellence range.

The selection continues to grow each day as artisan makers produce limited-edition bars from cacao that farmers cannot grow enough of to enable a chocolate maker to add a bar to its main line. Cuyagua, for example, is a tiny region in Venezuela adjacent to Ocumare de la Costa. Its beans are too few in number to become a regular mainstay bar in a maker’s inventory, so companies such as Scharffen Berger and Amano produce bars in limited edition runs.

|

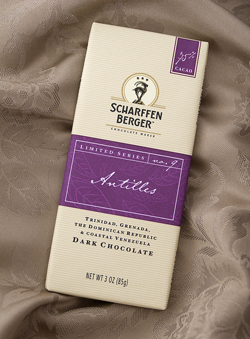

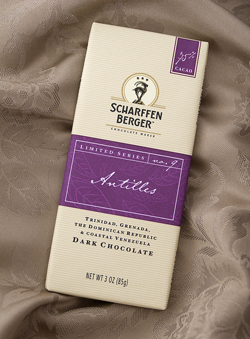

Antilles is an origin bar made of beans from the Caribbean. |

And it’s not just “name” companies whose bars you’ll buy at the store. Companies like Callebaut, a leading producer of high-quality couverture from Belgium, produce a selection of origin couvertures that chocolatiers remold into their own bars.* Callebaut and other business-to-business producers don’t sell to consumers under their own name, but make the chocolate that you may enjoy under many other brand names.

*It’s an industry standard for chocolatiers and chocolate companies to produce bars made from couverture by another company such as Callebaut or Belcolade. Once purchased, the couverture is melted, tempered, molded into bars and sold under the company’s name. This practice is very common and only acceptable if the company remolding the couverture does not claim to be a bean-to-bar producer.

The Concept Of Terroir

In fact, the world of fine chocolate has borrowed several principles and methodologies from French viticulture. Among the most basic is that of terroir (tair-WAHR), the concept that flavor is affected by geography, including microclimate and soil. Plant genetics and post-harvest processing methods are also key. It’s not uncommon to hear, for example, that high concentrations of phosphorous in the soil and varying fermentation practices contribute high acidity to chocolate, or that certain drying techniques are responsible for smoky notes in finished chocolate.

Continue To Page 3: Blended Vs. Unblended Bars

Go To Article Index Above

Lifestyle Direct, Inc. All rights reserved. Images are the copyright of their respective owners.

|