Is there a more delicious dessert than a dish of ice cream? Imagine the labor of making it before the days of electricity and freezers. Photo by Dusan Zidar | CSP. Is there a more delicious dessert than a dish of ice cream? Imagine the labor of making it before the days of electricity and freezers. Photo by Dusan Zidar | CSP.

July 2006

Last Updated July 2017

|

|

The History of Ice Cream & The Ice Cream Cone

Page 2: The Renaissance Gives Birth To Ice Cream

This is Page 2 of an eight-page article on the history of ice cream. Click on the black links below to visit other pages.

1500s: The Renaissance Gives Birth To Ice Cream

-

It took until the 1500s in Florence for architect and set designer Bernardo Buontalenti to invent gelato, the forerunner of today’s ice cream, enriching the sorbetto with cream and eggs. Its spread to the rest of Europe, starting with France, is attributed to another Italian, Catarina de’ Medici, who married the duc d’Orléans, the future King Henri II of France in 1533, and is said to have brought it to the court of France. According to the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA), a product called “cream ice” appeared regularly at the table of Charles I during the 17th century. The first recipe for flavored ices in French appears in 1674, in Nicholas Lemery’s Recueil de curiositéz rares et nouvelles de plus admirables effets de la nature.[2] In 1694, recipes for sorbetti were published in Antonio Latini’s Lo Scalco alla Moderna (The Modern Steward).[3] Recipes for flavored ices begin to appear in François Massialot’s Nouvelle Instruction pour les Confitures, les Liqueurs, et les Fruits, starting with the 1692 edition. Massialot’s recipes result in a coarse, pebbly texture. However, Latini claims that the results of his recipes should have the fine consistency of sugar and snow.

[2]Reay Tannahill, Food in History, revised edition, Three Rivers Press, (1995)

[3] Cadbury Ice Cream. Cadbury Trebor Bassett (2006)

-

However, no historical evidence exists to support either the de’ Medici or Charles I story: both tales begin to be told in the 19th century. But frozen desserts were the pleasures of rulers and royalty. It wasn’t until 1660 that a Sicilian restaurateur named Procopio served an iced dessert to the general (wealthy) public at Café Procope, the first café in Paris. The recipe blended milk, cream, butter and eggs.

-

Like most new foods—tea, coffee, sugar, chocolate—ice cream was for the first one or two hundred years a pleasure of the wealthy. Only they could afford to purchase ice that was cut in the winter and stored underground to make ice cream in the warmer months. Only the wealthy had chefs who knew the secrets of making ice cream and staff to undertake the labor. Refined sugar also was very expensive.

-

Before the development of modern refrigeration, ice was cut in large blocks from lakes and ponds during the winter and piled up in holes in the ground or in wood-frame ice houses, insulated by straw. Making ice cream was quite laborious. Enough ice had to be chipped by hand and packed with rock salt to fill a large tub, into which another pot of cream, milk, sugar and flavoring was placed (analogous to the construction of the classic crank ice cream machines). The ice cream was stirred by hand. The temperature of the ingredients was reduced by the salt and ice slurry below the freezing point of water, which turned the flavored milk and cream into smooth, frozen ice cream.

|

|

18th century ice cream maven Dolley Madison, wife of President James Madison. She served strawberry ice cream at Madison’s second inaugural banquet.

|

-

The ingredients had to be stirred constantly with a long spoon for hours, so they would turn to ice cream but not freeze into ice crystals. There was no refrigeration to keep the final product frozen—it needed to be served shortly after it was finished. This was a half-day of labor so the wealthy could enjoy five minutes of ice cream.

-

The first written reference to ice cream in the U.S. is in a letter from William Black, who wrote in 1744 of a dinner at the mansion of Governor William Bladen of Maryland, citing a “rarity” of ice cream with strawberries for dessert. The first advertisement for ice cream in this country appeared in the New York Gazette on May 12, 1777, when confectioner Philip Lenzi announced that ice cream was available “almost every day.” Records kept by a Chatham Street, New York, merchant show that President George Washington spent approximately $200 for ice cream during the summer of 1790. Inventory records of Mount Vernon taken after Washington’s death revealed “two pewter ice cream pots.”

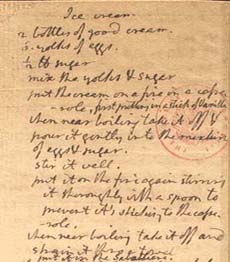

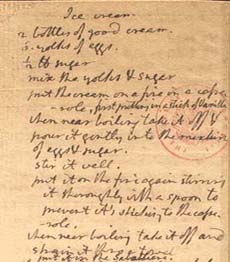

- Thomas Jefferson, a passionate gourmet who brought back many recipes from France, was said to have an 18-step recipe for an ice cream delicacy that resembled a modern-day Baked Alaska. That has not survived, but his recipe for vanilla ice cream, written in his own hand, is in the Library of Congress; his recipe for Savoy cookies to accompany the ice cream in on the back of the page. A portion of the recipe is shown at the right; click here for the entire document. He also brought 200 vanilla beans back from France (although they were imported from Mexico).

|

|

Thomas Jefferson’s recipe for ice cream, written in his own hand. It is in the Library of Congress.

|

-

Dolley Madison (shown above in an 1804 portrait by Gilbert Stuart), one of the greatest Washington hostesses, arrived in town during the Jefferson administration when her husband, the future President James Madison, was Secretary of State. She loved ice cream and served it often. Records note that ice cream was served in warm pastry. A magnificent strawberry ice cream dome was served at President James Madison’s second inaugural banquet in 1813.

Continue To Page 3: The Ice Cream Freezer

Go To The Article Index Above

Lifestyle Direct, Inc. All rights reserved. Images are the copyright of their respective owners.

|