Vinegar 101

Page 2: How To Make Vinegar

This is page 2 of a five-page article; here, how vinegar is made, and what contributes to its sourness (astringency). Click on the black links below to visit other pages.

How Vinegar Is Made

Vinegar is the end-product of a chemical reaction that occurs when bacteria (Acetobacter aceti) come into contact with alcohol. The bacteria turn the alcohol to to acetic acid and water. It is the alcohol turned acidic which provides vinegar’s unique taste. While acetic acid provides the vinegar with its primary taste component, it is the nature of the actual alcohol itself that gives the vinegar its specific character.

|

|

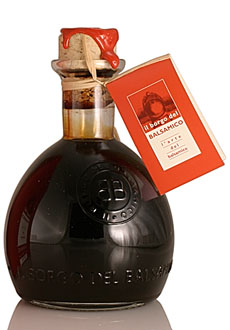

Balsamic vinegar production at Villa Gaidello, a working farm organic farm in Italy’s Po River Valley between Modena and Bologna. It has a restaurant and restaurant and guest rooms, for individual travelers or corporate meetings. |

Vinegar can be produced or generated in a number of different ways. It can take months with a hit-or-miss outcome; so by 2000 B.C.E., much vinegar was produced commercially by vinegar “masters.” Even so, success was not guaranteed. It was not until medieval times in Orléans, France, that a method was perfected, still used today for low-volume, high-quality batches.

The Classic Orléans Method

The Orléans Method involves placing a barrel on its side, filled to the three-quarter mark with diluted wine or beer and the all-important vinegar starter, or “mother” (mère de vinaigre) from a previous batch.* Two large holes on either side of the barrel admit the oxygen required for the chemical reaction. They are covered with screens to keep curious critters away during the initial aging period, during which time the barrel sits inert for two to three months at about 85°F. Then the entire content minus 10% or so (which is used as starter for the next batch) is poured through a spigot inserted into one of the two holes and bottled.

*The “mother” is a film of living bacteria on the surface of the liquid being soured. Mother can also grow in bottles of vinegar at home, especially those that have been sitting for a long time in a warm, dark environment. While unattractive, mother is harmless and believed to be beneficial to digestion. Refrigerating vinegar will slow or stop the formation of the mother. You can decant vinegar into another bottle, clean the bottle with the mother, and pour the vinegar back in.

Modern Vinegar Production

More modern (read: artificially accelerated and cost-effective) techniques for generating vinegar involve replacing the wooden barrel altogether. Mass production employs a giant vat into which a lesser quality wine is sent via a funnel lined with wood chips, called “trickling.” This setup allows the wine to pick up wood flavor nuances while exposing the mixture to much more oxygen as it makes its way down. The technique decreases the average production time from months to days.

The Astringency Of Vinegar

The “sourness” or acidic astringency of vinegar is determined by the amount of acetic acid produced during the chemical reaction. The amount and intensity of the acid, in turn, depend upon what ingredient was used to make the vinegar. On the tartness scale:

- Distilled white vinegars are always the strongest and most astringent

- Wine vinegars come in second

- Beer and cider vinegars and malt vinegar fall somewhere in the middle

- Rice wine vinegars are milder

- Balsamic vinegars are the most mellow

It is important to note that the quality of the ingredients, processing style, aging and bottling will affect the ultimate taste of the vinegar; so the tartness ranking is relative.

With a taste penchant for all things acetic, I grew up loving vinegar for its bright and sour taste. I loved what it felt like in the mouth and then in my stomach. I would literally drink red wine vinegar from the bottle (when no one was looking) and add it as a topping to any non-dairy meal.

Over time, my desire for such a sensation has been sated, and it is the more artfully produced product that moves me and my somewhat more discriminating taste buds. Balsamic has unsentimentally replaced red wine vinegar in most of my dressings and marinades. I do throw some high-quality red into the mix on occasion, for old time’s sake.

That vinegar is still such an essential ingredient after so many millennia is a tribute to its taste and versatility. Perhaps “she” needn’t lie about her age after all.

Continue To Page 3: Types Of Vinegar ~ A To C

Go To Article Index Above

|