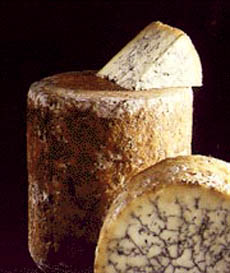

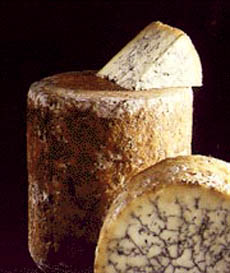

This gorgeous, creamy Stilton cheese from Cheese begins life with the help of bacteria in the starter culture, in this case Lactococcus lactis. The blue veins are caused by a mold, Penicillium roqueforti, which are added to the formed cheeses. This gorgeous, creamy Stilton cheese from Cheese begins life with the help of bacteria in the starter culture, in this case Lactococcus lactis. The blue veins are caused by a mold, Penicillium roqueforti, which are added to the formed cheeses.

|

STEPHANIE ZONIS focuses on good foods and the people who produce them.

|

|

January 2006

Last Updated May 2018

|

|

Cheese Starter Culture

Mesophilic & Thermophilic Dairy Bacteria Are Critical To Great Cheesemaking

A Little (Starter) Culture

Someone once wrote that it isn’t a good idea to inquire too closely into the making of both laws and sausages. I’d probably add cheese to that list as well. As we all know, milk is the foundation of cheese—no problem there. But one of the big determinants of cheese flavor is the starter culture selected by the cheesemaker. A starter culture is a combination of dairy bacteria added to the milk. These bacteria consume lactose, or milk sugar, and in return, excrete lactic acid. In sufficient amounts, lactic acid will cause coagulation of the milk. Rennet, which we’ll discuss next month, is often added to help this process along.

Properly acidified, the milk separates into curds (solids) and whey (liquid)—the first step in making cheese. Between these bacteria and the molds so necessary for so many of the cheeses we love today, it’s a wonder to me that anyone in the contemporary American germphobic society eats any type of cheese at all. But let’s look a little more closely at starters, what they are, and how they come into play.

As cheesemaking is an ancient practice, many types of cheese were already recognized prior to the modern era. However, in those times, replicating cheese flavor and character were especially problematic—it’s not always easy to do so today, but it was much tougher back then. People weren’t certain why some batches of cheese worked well and others didn’t.

Part of the answer lay in their limited choice of starter culture. When a fermented milk product had been made successfully, part of that day’s whey production was held back overnight. During this storage period, bacteria in the whey multiplied, and when this whey was introduced into the next day’s milk, ideally, it would function as a starter culture (this process has acquired the unattractive name of “back-slopping”). But because the process was so uncontrolled, cheesemakers could never be certain of the results. If temperature or humidity or the condition of the milked animals changed, the type of bacteria and the degree to which they proliferated could easily alter. And if the bacteria changed in type or quantity, who knew what kind of result you might get in your cheese.

|

Cheesemaking Today

Present-day cheesemakers have the considerable advantage of being able to rely on readily available starter cultures made in laboratories. Because these are scientifically formulated, cheesemakers can plan for a controlled input of both the amount and type of bacteria they desire into their milk. This is especially important in cheeses made from pasteurized milk, as pasteurization yields milk that is a “blank slate,” absolutely open to both beneficial and harmful bacteria.

|

The milk, starter cultures, rennet and blue cheese mould being stirred in the vat. Photo copyright Stilton Cheesemakers’ Association. All rights reserved. |

(I have read that cheeses made from raw milk typically do not require starter cultures, as the microflora naturally present in the milk will produce sufficient lactic acid for coagulation and distinct flavor, but I have been unable to confirm this.)

Lactic acid production in a cheese must be watched carefully. Some is required for most cheeses, but if there is an excess, the texture of the finished product will be crumbly. Conversely, insufficient lactic acid can result in a cheese with a paste-like texture. Proper quantities of lactic acid in milk also aid in driving whey out of the curds (a crucial step for any cheese other than those that are soft and unripened, such as cottage cheese) and assist in controlling pathogens in the cheese.

Types Of Starter Cultures

There are two basic types of starter cultures.

-

Mesophilic starters function at moderate temperatures and are used when curds will be warmed to a temperature not exceeding 102°F. The classic examples of cheeses made from such cultures are Cheddar and Gouda.

-

Thermophilic, or heat-loving, cultures, are employed when curds will be heated to a temperature as high as 132°F. Many Swiss and Italian cheeses use thermophilic cultures.

Within each basic type of culture, there are subcategories, such as a mesophilic specifically designed for goat cheese, or a thermophilic well-suited to Emmenthaler. If you make cheese at home, buttermilk can be used as a mesophilic culture; if you require a thermophilic culture, you can use yogurt. But these are impractical for most commercial cheesemaking operations. Incidentally, the exact culture blends used by cheesemakers in their particular products are often deep, dark secrets, but it’s hard to blame them for being so close-mouthed when so much of their finished cheese’s taste and texture depends upon these blends.

If you’re like many people, you may have become somewhat alarmed when I mentioned that starter cultures were dairy bacteria. Bacteria employed in these cultures are most often lactic acid bacteria. There are a couple of handfuls of genera of these bacteria, including some in the Streptococcus and Enterococcus groups. Wait a minute! Streptococcus as in strep throat? Enterococcus as in E.coli? Not exactly. Same genus, all right, but very different species, and not all species of these bacteria are harmful to humans.

The next time you’re enjoying a Stilton with your port or slicing up mozzarella for your famous fresh tomato salad, remember that culture isn’t always something found in a museum or an opera house. The humble bacteria that have helped make your favorite cheese what it is deserve positive recognition as human benefactors.

|

Company Of The Month: Fiscalini Farmstead

The Fiscalinis are fourth-generation cheesemakers in California, making making cheddars and aged parmesan under the Fiscalini Farmstead brand. If you don’t know, a “farmstead” cheese is an artisan-style product made from milk obtained from animals living on the farm where the cheese is made. There are a good number of places in California producing cheese these days, but less than a dozen are farmstead cheesemakers. Because the animals live on the farm, farmsteading gives a high degree of control over the milk used for cheese, and if there’s a good profession in which to be a control freak, it’s cheesemaking. All of their cheddars seem to have won gold medals, most at the most important cheese competitions.

|

San Joaquin Gold—part of the new California “gold” rush. |

A lot of space and attention is devoted to Cheddar cheese on the Fiscalini Farmstead website. I’ll confess I haven’t tried any of their Cheddars, neither their flavored varieties (which include a Tarragon, a Smoked, and a Cabernet-soaked variety called “Purple Moon”) nor their Bandaged Wrapped. What’s floating my boat these days is their signature San Joaquin Gold, one of the best multi-purpose cheeses I’ve encountered for a while now. Buttery-smooth, semi-hard, and terrifically flavorful, it makes a great snack and a brilliant macaroni and cheese. I’ve also used it for garlic bread. Because San Joaquin Gold isn’t sharp or pungent, kids enjoy it as much as adults do. The company’s “Retailers” page is, alas, worthless, but I can buy San Joaquin Gold locally in an upscale market, and I live nowhere near California. Better still, you can buy it online, by clicking on the links above. Buy some and join the new “gold” rush!

Lifestyle Direct, Inc. All rights reserved. Images are the copyright of their respective owners.

|