|

| |

The two bars produced by Patric Chocolate, one of seven microbatch chocolate producers in the U.S. Photography by Saidi Granados. |

| WHAT IT IS: Artisan chocolate bars, made in microbatches by “micro producers.” |

| WHY IT’S DIFFERENT: The artisans make only two or four different bars, each exceptional examples of single origin chocolate. |

| WHY WE LOVE IT: An opportunity to experience great single origin cacao chocolate forged by passionate artisans. |

| WHERE TO BUY IT: See individual references in the main review below. |

|

|

|

Beyond Artisan Chocolate:

Microbatch Bars

CAPSULE REPORT: If you’re a person with a passion for the world’s greatest chocolate, why not produce it yourself? That’s what the chocolate artisans in this week’s Top Pick have done—the majority of them as a second career.

They are not chocolatiers in the traditional sense. Their goal is not to make bonbons, nut clusters and truffles. They are chocolate purists whose goal is to produce the best chocolate bars in the world from scratch, traveling abroad to source raw beans, cleaning, roasting, winnowing, grinding, refining, conching, tempering, molding and packaging the chocolate—some with no help, some with a partner and/or a tiny staff. In the process, most have built or modified chocolate-producing equipment for results they could not otherwise achieve.

So, how good are these bars? They rank with the world’s best, including acclaimed small producers (but still, much larger than micro producers) like Amedei, Michel Cluizel and Pralus. If you like great dark chocolate, this is an eye-opening journey you can take without ever leaving your home. Read the full review below and learn more about these exceptional chocolate bars.

|

| |

|

|

THE NIBBLE does not sell the foods we review

or receive fees from manufacturers for recommending them.

Our recommendations are based purely on our opinion, after tasting thousands of products each year, that they represent the best in their respective categories. |

Make Your Own Chocolates

|

|

|

| Chocolate Obsession: Confections and Treats to Create and Savor, by Michael Recchiuti and Fran Gage. Even amateurs can achieve professional results with the guidance of two top chocolatiers, San Francisco’s Michael Recchiuti and Seattle’s Fran Gage. The book covers both chocolate and pastry. Click here for more information or to purchase. |

Making Artisan Chocolates, by Andrew Garrison Shotts. Shotts, the former pastry chef for Guittard Chocolate and the owner of Garrison Confections (one of our favorite boutique chocolatiers), shows readers how to create extraordinary chocolates at home through the use of herbs, flowers, chiles, spices, vegetables, fruits, dairies and liquors. Click here for more information or to purchase. |

The Art of Chocolate, by Elaine Gonzalez. A cooking teacher with decades of experience, Elaine Gonzalez has devised innovative techniques to put the art of working with chocolate within everyone’s reach. Even novices will soon be able to roll, curl, twist, coax and nudge chocolate to incredible heights of fantasy. Beautifully photographed. Click here for more information or to purchase. |

Beyond Artisan Chocolate: Microbatch Bars

INDEX OF REVIEW

|

MORE TO DISCOVER

|

Introduction

The chocolate bar was invented in 1847 by Francis Fry, the great-grandson of British chocolate company founder Joseph Fry. Until then, chocolate, throughout its history, had been only a beverage. Fry mixed some of the cocoa butter back into the cocoa powder and made a paste, which he molded. “Eating chocolate,” as it was called, was born. The Industrial Revolution, which reached its peak in the 1840s, ensured that factory machinery could produce as many bars as needed to feed the chocolate-hungry public. Companies grew large and successful selling chocolate to consumers as well as to pastry chefs and confectioners.

Manufacturing chocolate, starting with raw cacao beans—known in the industry as bean-to-bar production—was once an enterprise reserved only for companies that could afford expensive machinery and a built-in customer base to pay for it. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, when chocolate consumption in Western society was affordable to the average person and sales were taking off, companies such as Hershey’s Chocolate (1903) and Mars (1911) in the U.S., and Cadbury (1824), Lindt & Sprüngli (1845) and Nestlé (1860) in Europe filled a large market niche and quickly found a home in the mouths and hearts of millions of people worldwide. While there were many other manufacturers that did not become international names, these companies are still some of the most prolific and diversified producers of chocolate today.

Like oil and water, however, quantity and quality do not mix. Once a manufacturer starts producing at high volumes, the quality of the ingredients is generally lowered to meet corporate profit goals, not to mention that there is not enough of the finest-quality cacao beans to produce the quantity of chocolate that major corporations sell. Other pioneers, such as America’s Guittard (1868), France’s Valrhona (1924) and Venezuela’s El Rey (1929), emerged to produce chocolate at the level sought by top culinary professionals. Today, these fine chocolate manufacturers cater not only to professional chocolate makers and pastry chefs, but also to individual consumers who hunger for a top-quality chocolate bar.

In more recent years, they have been joined by producers such as Michel Cluizel (1948), Pralus (1955), Chocovic (1977*), Amedei (1990), Domori (1996) and Scharffen Berger (1998). These companies have been producing new and exciting chocolate bars and couverture that only a smaller scale of production can allow. We have tasted several chocolates sourced from a single plantation by Michel Cluizel; bars made from a single year’s harvest (i.e. “vintage chocolate”) by Valrhona; and through Domori, we even have the opportunity to discern how a certain variety of cacao tastes in three ways: a bean, a 70% bar, and even a 100% bar. And this is only the tip of the iceberg!

*The company was established in 1872 as a local chocolatier, but was acquired, changed its name and began supplying the pastry industry in 1977.

(You can learn more about the world’s top chocolate manufacturers in our article, House Tour: A Guide To The World’s Greatest Chocolate Producers.)

Inspired by the work of these artisan producers, a handful of American chocolate enthusiasts, some just out of college, have become micro producers (manufacturing three tons of chocolate a year, as opposed to the 100 or so tons of an Amedei, for example). They offer a very limited selection—some just two bars from different origins—but have a passion to create the single origin chocolate that can compete with the best in the world. And, by and large, they succeed.

The Major Categories Of Chocolate

Before we introduce our micro producers, let’s look at the American confectionary industry and the larger artisan chocolate companies mentioned above. Each of these companies makes couverture—blocks or disks of chocolate used by professionals—as well as chocolate bars for consumers. The differences among these types of bars are vast and technical, but the industry categorizes them by price per pound at retail. The official categories include:

- Mass Market, less than $15 per pound

- Mass Market Premium, from $15 to $25 per pound

- Gourmet, from $25 to $40 per pound

- Prestige, at $40 per pound and higher

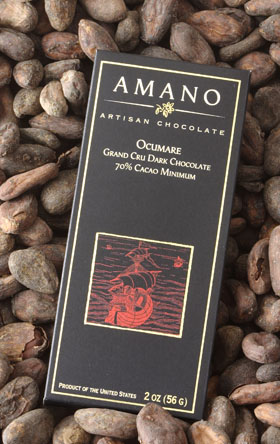

You can learn more about each of these categories in our review of Amano Artisan Chocolate.

“Artisan” and “Microbatch” are not official subcategories in the industry, because they are tiny, and the products fall under Gourmet or Prestige price points. The overwhelming tonnage of chocolate sold in the U.S. falls under the first two categories, Mass Market and Mass Market Premium.

Mass-Market Chocolate

These bars are churned out by large corporations such as Cadbury, Hershey and Mars, and are generally produced from beans that tend to be low grade, inexpensive and easy for farmers to grow. In the industry, they are referred to as “bulk beans,” or Forasteros, and account for 80-90% of worldwide cacao production. Flavor-wise, they’re usually non-complex and somewhat ordinary, though they are replete with the basic chocolate flavor we all know and love. Forasteros are used for candy bars, and all those unflavored bars that constitute a run-of-the-mill flagship bar for an industrial company such as Hershey’s milk chocolate, Cadbury’s Dairy Milk bar and a Mars Bar. A 1.5-ounce Hershey bar with a suggested retail price of 95¢ costs about $10.00 per pound of chocolate.

|

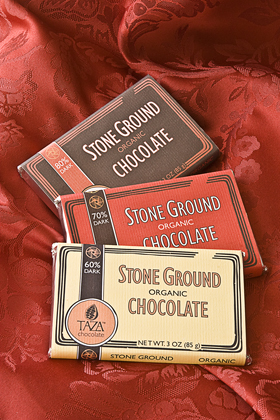

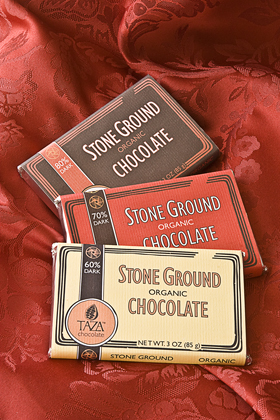

Taza’s microbatch chocolate falls under the Gourmet category, selling at $25 to $40 per pound (a three-ounce bar is $5.95). |

Mass-Market Premium Chocolate

This chocolate includes the premium lines of mass marketers like Hershey, as well as chocolate produced by somewhat smaller, independent companies that only produce premium chocolate, like Lindt. It is made in large factories. In the case of producers of mass-market chocolate, the beans are of finer quality than those that go into their main lines—and the price of these bars is also double or more, usually with a starting point of $2.00 to $4.00, depending on company and bean origin (beans from Venezuela can cost more than twice those from Belize, for example). Dove (produced by Mars), Hershey’s Cacao Reserve and Lindt are great examples that fit this category: delicious chocolate at an affordable, everyday price.

Gourmet and Prestige (Artisan) Chocolate

What retailers refer to as gourmet and prestige chocolate and define by price per pound, chocolatiers and consumers refer to as artisan chocolate, and define by quality and artistry. A producer emphasizes the flavor of the cacao, usually through meticulous blending of different origin cacaos or through the production of single origin chocolate, which is chocolate made from cacao sourced from a single origin (such as a plantation, country, region, etc.). Bars made from these beans are usually produced in lower quantities and for higher prices, usually in the $7 to $10 range per three-ounce bar. You can find many of them reviewed in THE NIBBLE’s Chocolate Section.

These are the bars of choice among connoisseurs, appreciated for their complex interplays of flavor and superior quality. They are made from the best beans: Criollo beans are often prized for their delicate and/or complex flavor, and the beans account for just 2% to 5% of worldwide cacao production (Robert Steinberg of Scharffen Berger pins this number at .1%). Trinitario beans are also revered for their flavor, and comprise 8% to 12% of worldwide cacao production. While Forastero beans make much of the world’s inexpensive chocolate, there are also some very fine Forasteros among the more than 14,000 subspecies of cacao. However, Alan McClure of Patric Chocolate advises against relying too much on trying to guess the species of the bean from the flavor of the bar, or conversely, trying to memorize flavor characteristics for the three bean species.

Microbatch Producers

|

Micro producer TCHO sells its bars for the equivalent

of $47 a pound—a 1.76-ounce bar is $5.00. |

There’s a new, coveted chocolate type to add to the categories above, engendered by America’s growing appreciation for fine chocolate. The world of fine chocolate has already borrowed nomenclature, tasting systems and the concept of terroir from wine and viticulture, but lately it is initiating a trend that has long been favored by beer connoisseurs: microbrewing. The U.S. microbatch movement launched in 2005, when U.S. microbatch pioneer Steve DeVries opened his doors. Others joined in, and ever since, chocolatiers in the U.S. have been making extremely fine chocolate on a much smaller scale (“microbatches”) than—and of comparable quality to—internationally-acclaimed artisan producers such as Italy’s Amedei and France’s Pralus. Sometimes with only themselves, or sometimes with a partner and possibly a tiny staff, these chocolatiers travel abroad to source the finest cacao they can buy, often from small farmers, and ship it home, where they clean, roast, winnow, grind, refine, conche, temper, mold, package and market the chocolate. As small start-ups, they start small, some with bars from two different origins, or perhaps two different percentages of cacao from the same origin.

While most micro producers don’t have the resources to market their wares beyond their home bases, growing connoisseurship, the locavore movement and websites that enable connoisseurs nationwide to obtain the products, have sustained these small companies.

As of this writing, we are aware of eight companies in the U.S. producing chocolate in microbatch fashion: Amano Artisan Chocolate (Orem, Utah), Askinosie Chocolate (Springfield, Missouri), DeVries Chocolate (Denver, Colorado), Mast Brothers Chocolate (Brooklyn, New York), Patric (Columbia, Missouri), Rogue Chocolatier (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Taza Chocolate (Somerville, Massachusetts) and TCHO (San Francisco, California). They were started by people who had no prior experience in the food business, just a passion for great chocolate.

While not part of this review, it bears mentioning that outside of the U.S., the most visible micro producer, and dean of microbatch chocolate bars, is the house of Bernachon in Lyon, France. Founded by Maurice Bernachon, who retired in 1953, the business is now run by son Jean-Jacques, with grandchildren Stephanie and Philipe working in the business. The bars are not sold in the U.S. but can be mail-ordered from France, or purchased in Paris. Italy’s Claudio Corallo is another micro producer, whose products are available from his U.S. website.

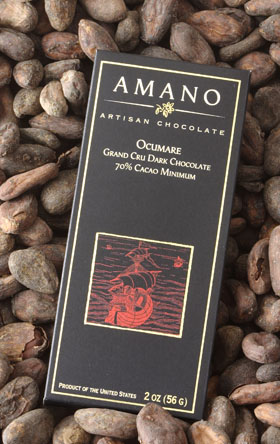

|

Amano Artisan Chocolate, a prior Top Pick Of The

Week, is one of eight companies currently micro-

producing chocolate in the U.S. Photo courtesy of Amano. |

You can read our review of Amano Artisan Chocolate, a prior Top Pick Of The Week, separately. Mast Brothers and Rogue Chocolatier will be featured in a sequel to this article. Today, there’s more than enough to chow down on, as we review five of these estimable producers of chocolate. You’ll note that the products are all chocolate bars—not other kinds of confections—because to chocolate connoisseurs, the excitement is to be found in the nuances of the single origin chocolate†, which are best appreciated in plain bar form. Some of the producers also offer nibs and nib confections (caramelized nib clusters from DeVries, for example). Askinosie has the largest line, offering bars, non-alkalized cocoa for baking, hot chocolate from both origins and roasted nibs from both origins.

†Single Origin Chocolate is made from beans grown in one particular area or region (i.e., the single origin). They can be a single variety of beans (e.g. Criollo and Trinitario) or a blend of varieties, but they get their unique flavors from the terroir of their region of origin.

Askinosie Chocolate

Askinosie was started in 2007 after its founder and namesake, Shawn Askinosie, left his full-time job as a criminal defense attorney to find something much more sweet. It took roughly five years for Shawn to finally find his passion, which ultimately landed him in the Amazon, searching for cacao. Trading the sterile walls and wooden benches of the courtroom for the lush flora and fauna of the Amazon, Shawn found his new vocation to be just as demanding, but much more rewarding.

Askinosie’s “stake in the outcome” business philosophy ensures that the cacao farmers earn fair wages. As well as paying the farmers higher than Fair Trade prices for their cacao, Askinosie also contributes 10% of net profits to the farmers. This profit sharing isn’t enough, though. Connecting the consumer with the farmer is also a vital aspect to the company’s operation. The website is chock full of pictures of the farms and farmers, and portraits of the farmers even grace the packaging of the bars as well. And to seal the deal, each bar is sealed with a strand of burlap from the bags in which the cacao beans were transported.

As far as bars go, Askinosie currently produces two single origin chocolates, each of which is available with nibs (called Nibble Bars—see photo below).

Askinosie pays tribute to the cacao farmers by featuring both of his growers on the packaging that contains the chocolate made from their beans. |

- Soconusco 70% is unique because it is currently one of the only chocolates produced with Mexican beans (aside from all the Mexican Porcelana bars). Soconusco, a region of the Mexican state of Chiapas that borders Guatemala, was once the center of quality cacao among early Mesoamericans, but eventually fell out of favor. With a new focus on the (now) Trinitario beans by Askinosie, the chocolate is extremely bold, à la Pralus, with a deep but subtle cherry undertone and a powerful chocolatiness.

- San Jose Del Tambo 75% cacao bar, from Ecuador (using the Arriba Nacional bean), on the other hand, is sharp and acidic yet still very chocolatey, as most cacao from this country usually is. Blackberry and plum flavors are at work full force in this bar, shouting in your face. It’s a wonderful and energetic chocolate that will make most people rethink this origin in the future. The nib versions of these bars are quite addictive and almost too easy to eat. The nibs are sprinkled on the surface of the bar, rather than mixed in, which makes the overall bar explode in the mouth. If you decide to buy one of these, you had better get a second...or maybe a third.

|

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE AMONG ARRIBA NACIONAL, TRINATARIO

& THE OTHER VARIETIES OF CACAO BEANS?

GET AN INSTANT EDUCATION FROM OUR

CHOCOLATE GLOSSARY

|

DeVries Chocolate

DeVries Chocolate is America’s pioneer micro producer of fine chocolate bars. Founded in 2005, the company was born of a hobby turned obsession; a chocolate-loving glass artist was transformed into a nationally-acknowledged chocolate artisan. On a trip to Costa Rica, Steve DeVries picked up some cacao beans with the idea of trying to make his own chocolate bars at home. The hobbyist was surprised to discover that his homemade chocolate, despite being quite rudimentary, was extremely complex and sophisticated in flavor. His experiment was enough to convince him to focus his efforts from transforming glass into art to creating edible gold from cacao beans.

Steve takes pride in being “100 years behind the times.” He went globetrotting to source equipment and to learn as much as he could about producing chocolate, eventually discovering that books published in the 18th and 19th centuries were his best guides. His equipment is old, too. It runs at slower speeds and lower temperatures, which is better at developing a chocolate’s flavor. New machinery produces chocolate faster, but not of higher quality.

When Steve introduced his first chocolate to the public, reception was overwhelming. His 77% Costa Rican was an instant hit at the Fancy Food Show, and since then, he’s produced many more varieties. Currently, DeVries produces a range of Costa Rican bars of 77%, 80% and 84% percentages, and a Dominican Republic bar of 77%, all from Trinitario beans.

- All of DeVries’ bars have a dark and brooding nature, with the Dominican 77% cacao bar probably the “lightest” of them all. It has lots of wonderful cherry flavors and even a tinge of olive, similar to Los Anconès (a Dominican Republic single origin), and some softer notes as well, notably peaches. It’s a fun and cheerful chocolate despite its darker persona.

- The Costa Rican 77% cacao bar is lovely, too, boasting a rum-like flavor and supportive tropical fruits such as pineapple.

- The Costa Rican 80% cacao bar was roasted at a higher temperature, and it shows, as the fruits even out and become barely discernible while nuttier notes take control.

- In the Costa Rican 84% cacao bar, the tannins are more prominent and the fruit is even less noticeable, making the chocolate very serious and stern.

Regardless of bar, all flavors lie low, and never scream at you. DeVries prefers subtlety and calmness, which makes tasting a contemplative and very relaxing experience.

|

Steve Devries, the “father of microbatch chocolate” in the U.S., produces four bars with very different flavor profiles. |

CHERRIES? OLIVES? PLUMS?

WHAT OTHER FLAVORS ARE FOUND IN PURE CHOCOLATE BARS? SEE THE

FLAVORS OF CHOCOLATE

|

Patric Chocolate

Not only does Missouri, “The Cave State,” have more caves and caverns than any other state (5,700+), but it has more micro-producers of chocolate as well (two, Askinosie and Patric). From the city of Columbia comes Patric Chocolate, founded in 2007, owned and operated by Alan McClure. The name of the company is rooted in Alan’s middle name, Patrick, but Alan removed the “k” so it would sound less Irish because, he explains, “The Irish are not historically known for their fine chocolate-making abilities.”

And until recently, neither have Americans. As we pointed out earlier, most chocolate in America is produced with quantity in mind rather than quality, which means that most connoisseurs have been faced with European-made chocolate, if they want variety beyond Guittard and Scharffen Berger.

Patric’s tag line, “French tradition, Italian innovation, American revelation,” draws reference to Alan’s admiration for France’s quality and artisanship and Italy’s innovative spirit and energy. As for the American revelation part, Alan claims it’s more of an aspiration to create a huge step forward in American chocolate-making through the culmination of French and Italian practices. It’s his way of doing so, and thus making a big difference in how we all eat our chocolate.

Patric produces two chocolate bars, both from Madagascar, a 70% and a 67%.

Patric, like Amano, eschews the earthy package designs of other micro producers for glamorous boxes, suitable for gifting. No wrapping paper is needed—just tie a ribbon around the box. |

- The Madagascar 70% cacao bar is bright and crisp but turns darker the more it melts. Raspberries, plums and subtle hints of blueberries shine brilliantly here. It’s a very elegant and refined chocolate, emphasizing delicate flavor evolution and lightness all around.

- The Madagascar 67% cacao bar is darker, although it is roasted slightly less than the 70% bar. The flavor is slightly more masculine by comparison. Normally, Patric, like Domori, does not add extra cocoa butter to its chocolate, but the 67% is different. The 3% extra sugar in the bar demanded just a slight addition of cocoa butter to improve the mouthfeel. The overall package is different than the 70%, which shows how just minor modifications can dramatically impact chocolate made with the same beans.

The beans are Trinitario with strong Criollo germplasm.

|

- Patric Chocolate

Two 1.75-Ounce (50 gm) Bars Each Of 67% and 70%

(Total 4 bars)

$23.00†

Patric-Chocolate.com

Taza Chocolate

Taza Chocolate, founded in 2006, is unique among U.S. micro-producers. Instead of focusing on refined bars, Taza leaves its cacao in a more unadulterated form. The company makes rustic-style chocolate, as it was made from the creation of the first chocolate bar in 1847 (by the Fry Brothers in Bristol, England) until the invention of the conche in 1879. “Rustic style” means a certain amount of gritty texture, not from external sources but because the early processing was not sophisticated enough to break down all of the particles in the chocolate. Taza chocolate bars give us an idea of what chocolate might have tasted like prior to Rodolphe Lindt’s discovery of conching, a refining of the chocolate paste through uninterrupted stirring, which makes it ultra-smooth and creamy. (Take an in-depth look at the chocolate-producing process.)

A vision of founders Larry Slotnick and Alex Whitmore, who had management positions at a car-sharing service, Taza grinds its cacao in traditional Mexican molinos (stone grinding mills) and ends the processing journey at another set of refiners to smooth out the sugar particles. Once the second grinding is over, that’s it: there’s no conching for these beans. Also setting Taza apart is its extremely light roast, which is administered to preserve as much of the inherent fruitiness as possible. The end result is a chocolate bar that has a not-too-gritty texture and a fruitiness that’s as intense as a nuclear blast.

We were able to sample the 70% and 80% bars, both made from Dominican Republic cacao.

-

The Dominican 70% cacao bar is where Taza’s-ultra conservative roast is most noticeable. The chocolate is intensely fruity, shooting off strawberries or pomegranate in every direction with a lovely—and equally strong—counter of bitter almond. It gets spicier toward the end and darker as well, but overall the bar is light as a feather.

- The Dominican 80% cacao bar is also light but noticeably darker, showing a strapping tone of black cherries that takes the shine off the glaring acidity. The chocolate is still light, but the 10% extra cocoa solids give the bar a darker personality, one that makes the chocolate slightly more balanced and, as a result, more accessible. It has just the right sweetness level, too, which is due to the high acidity, thus eliminating the need for extra sugar. As a result, you can get a low-sugar, high cocoa content bar with a very manageable flavor that most bars of this class can never achieve.

|

Rustic-style chocolate will give you an idea of how people enjoyed chocolate before Rodolphe Lindt invented the conche. |

- People who don’t like high-percentage cacao bars can enjoy the Dominican 60% cacao bar, which is considered semisweet chocolate, as opposed to the 70% and higher cacao content bittersweet chocolate in most of the other bars in this review. (Patric makes a 67% Madagascan bar.)

The company also makes Mexican chocolate disks—the first “gourmet” Mexican chocolate that we’ve come across—that can be turned into a delicious beverage.

- Taza Chocolate

3-Ounce Bar

$5.95†

(Equivalent to $32/pound)

- Mexican Chocolate Disks (see photo below)

2.6-Ounce Disk

$3.95†

TazaChocolate.com

TCHO

TCHO (pronounced “cho,” rhymes with “row”) gives California its second bean-to-bar company after Scharffen Berger, which arguably is responsible for initiating this small-scale bean-to-bar trend in America. (Theo Chocolates, another Top Pick Of The Week, is an organic bean-to-bar producer in Seattle.) TCHO was started by Timothy Childs, a space shuttle technologist, and Louis Rossetto, co-founder of Wired Magazine (the “T” stands for technology, the CHO for chocolate).

After Timothy left the aerospace industry, he co-founded Cabaret Dessert Chocolates, which became known for its elegant, diamond-shaped white and dark chocolate truffle confections in an eye-catching red box with a Toulouse Lautrec dancer on the cover. But he decided leave the confections end of the business to produce chocolate from the bean. Rossetto provided much-needed help to get the business off the ground, and eventually the two found themselves tweaking traditional chocolate-making equipment with high-tech modifications to keep the machinery (and thus, the chocolate it produces) ahead of the game.

Vote for your flavor preferences, and the producers may change the recipe. |

Where TCHO also differs is in its marketing and product development strategy. Rather than hire a focus group to tweak a chocolate’s flavor to perfection, or use their own palates, as the other microbatch producers do, TCHO conducts public “beta testing,” a product development process that allows the purchasers to give feedback that the company uses to refine the product. For example, if a majority said “too bitter,” the company would work on removing the bitterness from the bar. Not only does this save TCHO money, but it also creates free advertising hype for when the final bars are ready.

- The first bar in the line is called “Chocolatey,” a 72% cacao single origin bar from Ghana. It has an awesome chocolatey flavor with blueberries in the fore. In beta version, vanilla was also a strong element, which Timothy promises to tone down in the final recipe. After all, TCHO is listening to customer feedback!

|

Chocolatey is now out of beta test: the recipe has been finalized and the initial results are certainly promising for this newest micro producer (which opened its doors just seven months ago, in December, 2007). The company’s next bar, Fruity, will debut for beta testing in a few weeks, followed by Nutty and Blend. Stay tuned!

- TCHO Chocolate

1.76-Ounce (50g) Bar

$5.00†

(Equivalent to $45.00/pound)

TCHO.com

We conclude with the question, “can you drink a microbrew (beer) with your microbatch (chocolate)?” Absolutely! Beer and fine chocolate are an excellent combination. In the June issue of THE NIBBLE, we’ll present pairing ideas that would make a memorable Fathers Day event. But you don’t need a holiday to try these fine microbatch bars. Order a bunch and start consuming today.

— Peter Rot and Karen Hochman

FORWARD THIS NIBBLE to chocolate connoisseurs and those desiring to develop connoisseurship.

†Prices and product availability are verified at publication but are subject to change. THE NIBBLE does not sell products; these items are offered by a third party with whom we have no relationship. This link to purchase is provided as a reader convenience.

Askinosie’s Nibble Bar, made in both of its origin chocolates, is embedded with roasted cacao nibs. Askinosie’s Nibble Bar, made in both of its origin chocolates, is embedded with roasted cacao nibs.

|

Taza’s Mexican chocolate is melted down into Mexican

hot chocolate.

|

Find More Terrific Products In These

Sweet Categories:

|

Check Out These Other “Top Pick Of The Week” Chocolates:

|

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION, special offers,

contests, opinion surveys, THE NIBBLE

prior issues archive, product gift-finder and more,

visit the home page of TheNibble.com.

Do you have friends who would enjoy THE NIBBLE?

Click here to send them an invitation to sign up for their own copy. |

© Copyright 2004-2026

Lifestyle Direct, Inc. All rights

reserved. All information contained herein is subject to change at any time

without notice. All details must be directly confirmed with manufacturers, service

establishments and other third parties. This material may not

be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached, or otherwise used, except with

the prior written permission of Lifestyle Direct, Inc.

|

|

|

|